We’ve done a bit of a crash course in poetic craft and technique these past few weeks, but, of course, simply following directions doesn’t usually result in amazing poems, the ones that stick with you long after you read them. Laux and Addonizio note in The Poet’s Companion that “there’s something in a good poem that can’t be accounted for logically.’ They write:

Mystery, creativity, inspiration –these are the words that come to mind when we think about certain aspects of poetry that are separate from craft. These are things that can’t necessarily be taught, or learned. What we can do is to try and access that source from which they spring, to circumvent or suspend the logical, literal, linear mind with its need to control and understand everything.

As they go on to note, the Surrealists were champions of this “mystery, creativity, and inspiration.’ Perhaps no artistic movement has more fervently mined the potentialities of the imagination than the French Surrealist movement of the early 20th century. With their emphasis on irrationality, associative thinking, the energetic beauty of the bizarre, and the generative power of the unconscious mind, the Surrealists saw the conscious order (and proclivity for ordering) as not only a constraint on creativity, but also as producing ‘inauthentic’ and boring art. The unconscious mind–the site of the dream world, in all its chaotic glory–is, in their view, that dark strange well from which all ‘real’ art springs, and where the imagination can be truly “free.”

Andre Breton, perhaps the spokes-poet of the movement, wrote in his first manifesto that Surrealism is “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought.” You can read the first manifesto here. (That site features an exhaustive compendium of Surrealism, if you feel inclined to explore, but the manifesto is still the best place to start!)

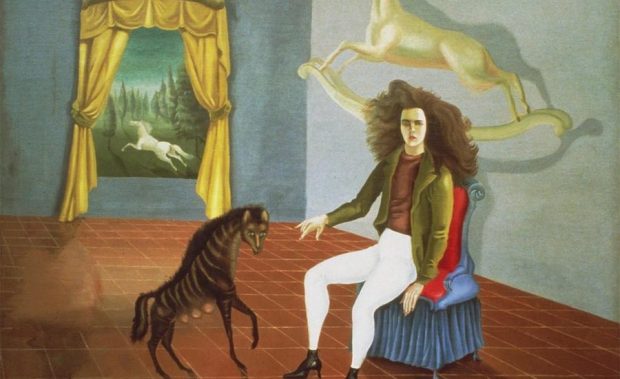

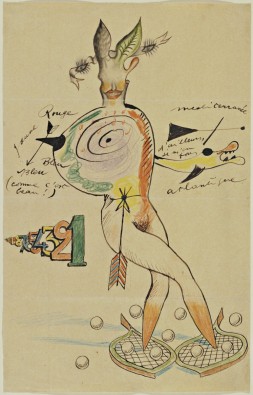

In championing automatism, the Surrealists embraced techniques that diminished conscious decision-making and embraced chance, play, and improvisation. Many of the techniques they used were communal games invested in the collective unconscious, such as Exquisite Corpse, an activity used to produce both collaborative drawings and poems, during which each participant contributes a component without being able to see what previous participants had produced. The collaboration below is by Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Max Morise, and Man Ray, courtesy of The Moma:

The Academy of American Poets has instructions for the literary equivalent here. While that exercise requires a group, other surrealist techniques included the cut-up method (cutting up text, say, from a newspaper and rearranging it into a poem) and sessions of free association, during which the writer writes and writes and writes without stopping to think about what he or she is writing. You might, for example, set your timer and free-write a poem for 15-20 minutes, without stopping or thinking about you are doing; then, write a second (refined) poem from the freewrite you’ve produced, choosing to keep what draws you and leaving the rest.

The worst place a writer can be is in a rut, and ruts are usually manufactured (or at least upheld) by boredom with our own work, or being so self-consciously stuck in our preferred poetic language and technique–or even what we imagine to be our readers’ desires–that we forget how to think outside our own boxes. Surrealist techniques may produce a bunch of silliness, but that’s part of their value: they bring a bit of fun to our own self-seriousness. They remind us to play, and how fun language can be, which is a valuable reminder when writing poetry is starting to feel a bit too much like work. And, in requiring associative thinking, they encourage discovery, and may also help us to write poems (or at least images, or figurative language) that surprise us in their transformations.

Furthermore, these techniques can help us to begin a poem that we can go on to finish more self-consciously. They can, for instance, generate new images and metaphors that we can use in a draft–ones that we were unlikely to create on our own–and open doors to deep memories we have since suppressed.

I highly recommend starting a dream journal, as Laux and Addonizio suggest in their Ideas for Writing section. Even if you don’t turn any into poems, just recording dreams alone can strengthen your poetic imagination.

Write your reading response on one of the poems from Packet #5, paying special attention to strangeness and surprise.

Christy Barrett

This week, I’ll admit I intended to respond to Implications for Modern Life by Matthea Harvey, but that poem flew right over my head. So… on to plan B: Iskandariya by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. This poem is so childlike and innocent. As I read it, I pictured a little girl with pigtail braids disappointed in God but not wanting to be. I love all the descriptions she uses for the scorpion she did not and would not ask for. I smiled as I read it. It’s like when you are terribly disappointed in something as a kid… this is how I would have acted in my tantrum. I got a fish tank for my birthday when I was eight, and I remember telling my friends in my childlike foolishness: “What am I gonna do with a dumb, ol’ fish tank? And who heats up water for fish anyway? The ocean ain’t heated. That was a waste of money. A fish tank heater? How dumb. And I didn’t even get to name the stupid, ugly things. The evil stepmother did. Lucy and Ethel. Dumb, stupid names!” Of course, Brigit Pegeen Kelly says it better than I ever did, but she wanted fish, so we are clearly two different people. Again, we have a poem that doesn’t feel obligated to rhyme or dance on the page. And I love that. But what child compares the lungs of a scorpion to a manuscript so beautifully? I really enjoyed this poem. Sometimes the gifts we receive from God or elsewhere are just enough to change our lives… or maybe just our perspectives. (Lucy and Ethel were electrocuted when I broke the tank heater while cleaning the tank accidentally, of course. RIP dumb, ol’ fish.)

Miranda Reynolds

I was very drawn by the surprising conclusions drawn from the discussion of a scorpion in Kelly’s “Iskandariya.” The poem uses the stereotypical malevolent nature of a scorpion advantageously, choosing to draw unique conclusions on its personality instead of using its common association, a ferocious, venomous creature. To build the poem into a stranger conclusion of the scorpion—it is shy and defensive, not destructive—Kelly starts by listing the logical conclusions and then negating them. For example, one line that used this strategy particularly well was “but not…despite the dark gossip, a lover of violence and a hater of men.” I think that Kelly’s use of a more commonly associated theme of scorpions before the poem’s own conclusion frees the work to explore new ideas more easily. Part of the difficulty of surrealist writing is embracing strange and contradictory ideas, which is why Kelly’s writing the logic to free the poem from staying within its confines could be useful for exploring surrealist writing myself.

Secondly, this poem uses imagery extremely well in building a more complex picture of the scorpion, by the end an abstract, inorganic bookshelf. One of my favorite examples is at the end where Kelly takes a simple metaphor, “his lungs are holes,” and continues to build on this idea, “holes which open and close…stiffened membranes…pages of a book.” Each new image connects to the previous one while also bringing new insight that mutates the old image, like playing telephone. Then, Kelly magnifies the imagery into a bigger picture of the scorpion, juxtaposing the single book with “the library at Alexandria, which burned.” With these final words, Kelly suggests that the scorpion is fated to ominous destruction and while it is not clear exactly what this means, the poem seems to travel full circle to the common logic of a malevolent creature.

Ainsley L Smith

For this week’s reading response, I decided to read the poem, Iskandariya by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. This poem is very interesting to me because of the imagery that is used but also the conclusions that Kelly draws from the simple scorpion. In the very beginning, we learn that the protagonist was given a scorpion instead of a fish, and we venture onto many different theories as to why this happened. The author wanted something sweet but instead was given something else, a venomous creature. However, we learn that this creature is also kind.

When I think of a scorpion, I think of something scary, disgusting, poisonous, and hazardous. Kelly makes that point in the beginning, talking about the quick conclusions that humans make. Then, she flips it totally around, focusing on the beautiful, meek characteristics of the scorpion, which to me is super surprising. She explains that the creature is shy, who is scared of sunlight, who will only become dangerous when in danger. Kelly uses a great sense of irony that leaves so many surprising conclusions throughout the poem, making me second guess my first thoughts.

Her imagery around the complexity of the scorpion was also surprising and enchanting to me as a reader. She talks about the holes in the scorpion, from where they breathe. Plus, she somehow compares it to pages of a book so successfully, which painted a new picture for me. The scorpion transformed into a library, the library at Alexandria, which evidently burned. Those last few words/lines totally switched the idea of the poem, from a shy creature, to a body meant for turmoil. It was a surprising and interesting end to the poem.

Casey Fetterhoff

Right away, “Implications for a modern life” starts out strange. The words “Ham flowers” immediately stick out and make the reader go “Huh?” and from there I just had to see what the author was on about. The truth is, the rest of the poem is a heartwrench, and the ham flower intro turns out to be much more sinister. The strangeness of the poem sticks out as a description of sights we are by now used to seeing, in a way that highlights how strange they really are. By bringing out every gory detail in a disguise, we finally see the details for what they truly are. While I do not envy the author the clarity of thought that brought them to write this, I admire the message they manage to convey in such a short passage. It’s doubtlessly a passage that will be on my mind, for a while.

Sarah corbett

I’m going to respond to the ‘the implications of modern life’. I’m having trouble fully deciphering the poem, but I’m pretty sure it’s about animal consumption. The reading response asks us to focus on strangeness and surprise, so I’m going to focus on that. This poem was more strange than surprising. Everything in it was meant to be made from animals, except for the sleeping horse. I’m not really sure what the sleeping horse was meant to represent, but the symbolism of everything being made with animal parts really sat with me. Part of my paper in my other class has to do with vivisection, so I’ve had animal abuse on the brain for quite some time now, and there is something about this very surreal picture that this poem painted that made me feel frustrated all over again by our system of animal consumption. I feel like the speaker of the poem was trapped in a world where they couldn’t do much to change the system, but were trying to do the best they could to show kindness to animals, and I really feel that. It’s hard to live in this consumption based world without causing harm to something, even indirectly.

Nadia Finley

I am responding to “Implications for Modern Life,” by Matthea Harvey. Wow is this poem bizarre. The whole thing feels so specifically unique, like an avenue of thought that could only be explored if caught before one passed it–a temporary blanket and pillow fort in the mind that conceals an expansive, unreal, crooked dream world inside. Reading the piece, I am reminded of what my sister says when I go off on some out of nowhere, nonsense rambling, “Where is this coming from?”

Where is this coming from and what is she trying to say? Though I may not fully understand the poem, I see. I see the ham flowers with their veins and little meat sunset petals; I see the platelet lard barge sailing down the blood stream; I see the oily river and the pasture flecked with pink; I see that BLEEDING BARN. It’s all so sticky pink and gross. I can see the poem, feel the poem, despite being completely and utterly lost on it’s meaning. I don’t have to understand why the speaker first denies any connection with the ham flowers before stating that she made them to understand that something is not right with her. Nor must I know the speakers intentions for the horse to feel pointedly concerned for the creature. Harvey has created a world that is both immersive and illusive. The piece speaks so clearly to the feelings (I feel sick just thinking about the tilted blood tinted farmland), yet it also speaks to something beyond emotions. Nonsense for the sake of randomness is noise, but the subconscious brings out an idea, even if it is an incoherent abstraction of some point.

Ta'Mariah Jenkins

The poetry piece I’ve decided to review is, ” The Living.” To be honest, I have never felt so consciously aware, in addition to creeped out. I can’t completely say I understand what is being said, but the author’s words are so vivid and lively, that I literally shuddered the first time I read it. The imagery seems somewhat inhumane and strange. I get lost within the text and I can say I was surprised how the character in the poem describes their surroundings. Explaining the scenery and comparing them to different types of scenarios is such a good strategy for imagery.

After reading this piece, it really does sound as strange as a dream. I had mentioned how this piece seemed so inhumane and strange. That kind of imagery really seems dream-like and not comprehensive. At first, I was looking for the meaning behind the text, but I couldn’t come up with anything that was understandable. The wording had seemed somewhat foreign, meaning it was hard to understand and I couldn’t place where the author was coming from. This poem is different from the other poems we have read before because the use of imagery is so extreme. The poem portrays imagery so far to the point where it takes more time to understand.

Jewel Blanchard

For this week’s reading response, I will respond to, A Speech About The Moon, by Chelsey Minnis. When reading this poem, for some reason I was reminded and brought to thinking of when I have nightmares. The strangeness in this poem makes me picture the speaker having nightmares. I picture the speaker going in and out of nightmares that are maybe created from the fear of some things. Like the crabs, where the poet writes about the speaker waking in the middle of the night to tell oneself that no crabs are coming towards them. The poem really reminded me of myself and what I fear. How sometimes I will over analyze something until I am having a bad dream over it. Then the poem also reminds me of how creative our minds are and how fun it is to be creative and think freely. Chelsey Minnis, I think, does an excellent job of constructing this poem and I really admire her last line. “I think, “The thoughts are terrible ballet teachers with canes.”” That line spoke volumes to me in the way that she uses the simile. It’s clever and makes sense. I definitely feel that way about my own thoughts sometimes.

Adeline Knavel

For this week’s reading response I decided to read “The Implications of Modern Life” in poetry packet 5. I’m not gonna lie, Matthea Harvey starts her poem out a little strange. I couldn’t decipher the meaning of it the first time I read it. It’s a strange poem but the strangeness and weirdness of it are what had drawn me into the poem and made me want to read it more. Matthea Harvey starts the poem off with words like “ham flowers” “little meat sunset”. Those immediately stuck out to me and made me think of random things like a pig or maybe something else. Almost immediately after this then the poem turns into a heart wrenching poem. There are strange descriptions being placed into the poem that sticks out. The calves wear coats so the ravens can’t eat them and gather seeds to burn them. These strange descriptions stick out and make you think about how weird this poem is. The author brought out every detail in a bloody and gore way that you can see what is really happening. There were many details in Matthea Harvey’s “The Implications of Modern Life” that made it focused on animals. I think the author is actually trying to love and help the animals but can’t because that’s not what she’s supposed to do.

Zofia Sheesley

I read A Speech About the Moon and it gave me a lot of childlike wonder and imagination feelings, it started off with such a powerful nostalgia, peter-pan thing. But it also feels like, the more you read, the more psychosis it feels. It feels a lot like a break-down like laying in bed, mind both blank and going a million miles a minute, breathing slow and fast at the same time, not having enough air in your lungs for your brain or body to function properly, eyes constantly tearing and crying but also stinging and in pain and dry. It feels a lot like that. Like someone is upset about growing up or they are upset about just something and they are thinking back on childhood and all of the crazy things that kids think and say and dream of. The intrusive thoughts that interrupt the wonder are so strong. The, “I have to be tormented” and “I have to die” cut through so deeply that it makes it all more visible and more real, I can feel and see and be exactly there. It’s a perfectly clear incoherent poem about nothing and everything. It’s how you feel when you don’t know what you feel and what you think when you don’t know what to think. It’s that in between and that rock bottom. But somehow it could also be the highest of good feelings, nothing to worry about, just thinking about whatever, thinking about the mood and fish and birds and being free to think and be alive. It’s whatever you want it to be because it’s so strange and out there and incoherent. It’s perfectly clear to the right reader.

Gabriel Miller

For the poem “Iskandariya,” I felt that the poem managed to be pretty playful with its surreal imagery while still focused. Upon looking into the title, it turns out that it’s translation of the word Alexandria. With this in mind, the scorpion feels much more integrated into the poem due to the allusions to the Library of Alexandria. As for the imagery itself, I really liked the abstracted relationship of man and God in the poem. I think that it was interesting to have the character forgive and rationalize God’s failure in fulfilling his wish, and show his growing acceptance of the scorpion. I think that having the perception of the scorpion evolve from a venomous monstrosity into a relaxed companion was an interesting choice of juxtaposition. Also, I think the description of the scorpion in being like the library helps to create a sense of sacredness in the animal.

Kyleigh McArthur

I’d like to respond to “The Living” because it was littered with imagery that stuck out to me. The one I remember the most is “My true face is that of a potato. I have many eyes, but see nothing.” This is such an interesting simile comparing your face to a potato, and yet it works so well. I would have never thought to make this connection, and I almost laughed the first time I read the comparison of a face and a potato. It is very different, yet it works and it’s unique. Then later the author says “There is no such thing as inner space… Maybe there are a few pockets between my kidneys or the lobes in my upper midsection but it’s tight.” This was very strange to read. I wasn’t expecting the inner space to be literal, and yet it became literal and surprised me. I think that is really good when you’re reading; to be surprised because it keeps me, the reader, interested and curious. I really liked this poem, it peaked my interest.

Devin Byrd

Kelly’s paths of reasoning are strange and at times a bit nonsensical, but they are understandable, and can be followed. Iskandariya seems to tell of the evolution of the author’s perspective on her initially unwanted and misunderstood pet scorpion. I’ve never really been one to find “creepy crawlies” detestable unless they are pests, and I am unable to empathize with her initial dislike of the scorpion, but I can understand her thoughtful transition from disgust to fondness. Kelly delivers it in a far more articulate and wordy manner, but the basic idea of what made her change her mind was that through experience with the scorpion she made the realization that the creature’s actual nature differed greatly from its false, villainous reputation as a compact creature of pure evil and malice. She is even able to relate to the creature, once she discovers that it only seeks to survive and live in lonely peace much like herself.

There are many portions of Kelly’s piece that reference works and entertain metaphors that fall outside of my own tastes, but I wouldn’t refer to any part of her work as strange. Just the product of a well-read mind with more eccentric affinities.

Johnny Bishop

So one poem that really stood out to me was The Living. The strangeness work relatively well in this poem. I think towards the end it gets more intense and real for the writer. surprise in this case is kind of hard but the sentence that described his face and the fact that he described seeing nothing so vividly to me fits in the poem very well. The sentence “When I try to explain anything some part of something, somebody dies.” draws you to the conclusion very well and ends it with a strangeness that works for a poem.

Anna Johnson

In “The Living” I am already caught by surprise when “dried arteries” is used to describe dead trees. It wasn’t something I expected to read. Once I read about the Midwest’s personality I saw an interesting way to describe it. “Like the face of someone I want love from, basic needs tied up in a cloth sack”. I think what makes this poem so strange is the words used to describe things. Like a face being compared to a potato or basic needs in a cloth sack which is all hard, dry, and clean at the same time. What comes up again are the physical insides of a person, which is talking about space between kidneys and how it is tight. I kind of got uncomfortable reading this because I generally don’t like to think about my insides have space and being tight. I thought this piece was very strange and it ended strangely too where we read “I drink with my eyes”. It was hard to make sense of it but I understand that what comes with strangeness and surprises is that it might be complex. It kept my mind occupied trying to understand it from a real-life perspective.

Curtis Wolfe

I’ll be responding to “The Living” this week. I decided to respond to this poem because it really drew me in within the first sentence. The imagery really stood out to me from the get-go. I stayed in. the Mid west for a short time in college and I could connect really well to the imagery that was placed in front of me. But I really didn’t see where the poem was going at in the end. It came across strange to me. I couldn’t tell if the speaker was talking about someone actually dying or talking about the land looking dead. But I ultimately enjoyed it.