I’m sure that many of you are eager to begin the fiction unit of the course. But before we start our stories, we need to remember what constitutes a “story.” We also need to consider how narratives are typically structured. Perhaps the most important element of the short story structure is conflict. This does not mean conflict in the sense of plot (such as warring military factions), but of character (such as, for example, the soldier who is in the military to fulfill his father’s wishes, but is afraid to die and conflicted about actually deploying). Something needs to be “at stake’ for your main characters; they must have an investment in their world that is unique and personal to each of them.

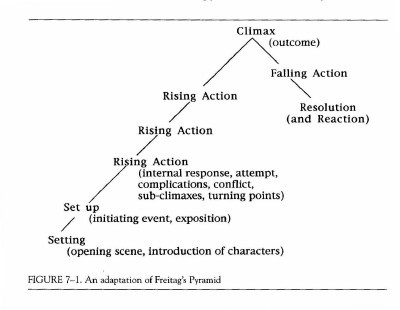

Once you understand what your story’s primary conflict will be, you must consider how you will build up to it–and resolve it. A formulaic narrative structure is not necessary to follow in every short story you write, but it is important for you to know that it is the standard structure, that what does not follow this structure is a deviation, of a kind, from an established formula:

Another way to look at this trajectory is:

- Set the scene for the conflict.

- Introduce the conflict.

- Deepen the conflict.

- Bring the conflict to its climax (the highest tension point).

- Release that tension (the denouement).

In this way, the conventional story expands and contracts–tenses and releases–like a muscle. And, of course, it must move.

But following a basic structure or formula, of course, is not enough to make a good story, one that others will want to read. Stories need to keep a steady pace that keeps readers interested, while not overwhelming them with too much action too quickly, or wrapping things up too quickly. Stories also need to connect with readers emotionally and psychologically; characters need to seem like “real’ people to your readers on the page, rather than just vessels for your plot or worldview.

So, how do you write a “good’ story? Here is some bare bones advice:

- Begin the story at the most opportune moment, usually in media res.

- Make sure and that the conflict is clear, that the story has stakes.

- Make sure to develop your characters into complex emotional and psychological human beings, rather than stereotypes or means to further plot points.

- End in a surprising or startling place. Don’t tie things up too perfectly at the end, or overstay your welcome.

Raymond Carver’s advice in “Principles of a Short Story’ is more complex, and hopefully more helpful:

-

“It’s possible, in a poem or a short story, to write about commonplace things and objects using commonplace but precise language, and to endow those things–a chair, a window curtain, a fork, a stone, a woman’s earring–with immense, even startling power.’

-

“No iron can pierce the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.’

-

“That’s all we have, finally, the words, and they had better be the right ones, with the punctuation in the right places so that they can best say what they are meant to say. If the words are heavy with the writer’s own unbridled emotions, or if they are imprecise and inaccurate for some other reason–if the words are in anyway blurred–the reader’s eyes will slide right over them and nothing will be achieved.’

-

“What creates tension in a piece of fiction is partly the way the concrete words are linked together to make up the visible action of the story. But it’s also the things that are left out, that are implied, the landscape just under the smooth (but sometimes broken and unsettled) surface of things.’

-

“Then the glimpse given life, turned into something that illuminates the moment and may, if we’re lucky–that word again–have even further-ranging consequences and meaning. The short story writer’s task is to invest the glimpse with all that is in his power.’

Remember also that developing characters requires more than simply giving backstory, or giving us their emotional reactions in the moment. Your characters need emotional inner lives, ones that exist before the story and will exist in our imaginations after the story. So, for example, consider how you might use characters’ memories to help us understand who they are at the time your story begins, or show us how they uniquely process the world around them. In your textbook, Donald Maass makes several strong points about the importance of maintaining an “emotional craft’ as you write. As he says,

Emotional impact is not an extra. It’s as fundamental to a novel’s purpose and structure as its plot. The emotional craft of fiction underlies the creation of character arcs, plot turns, beginnings, midpoints, endings, and strong scenes. It is the basis of voice.

The most important word to keep in mind is “complexity.’ In order to have complexity, your characters must have psychological and emotional layers. As Maass puts it, “Skillful authors play against expected feelings. They go down several emotional layers in order to bring up emotions that will catch readers by surprise.’ As you read Maass’s book, consider what it means for a person to be “real’ and “complex.’

I will not summarize his chapters for you–please read them before moving on–but I will note that a particularly strong example of “emotional craft’ you should note is the excerpt from Hemingway he includes in Chapter 2. As he writes, “Hemingway’s passage does not tell you what the point-of-view character feels. As Hemingway intended, he merely creates the experience, and we in turn feel something.’ Creating an emotional experience for your characters that your readers can vicariously experience is essential if you want your readers to connect deeply with your characters.

*

You only read one story for your reading response this week. Consider how Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral’ adheres to the advice he offers in his own essay on fiction, as well as Maass’s concept of “emotional craft.’

Sarah corbett

Growing up, I was always big into fiction, and it was usually teenage fantasy (Harry Potter, Twilight, House of Night, etc). When I got a little bit older, I started reading just regular fiction novels. My favorite author was Jodi Picoult, and I had almost all of her books at one point. I was obsessed. I could almost always be found engrossed with one of her novels; at lunch, in between classes, or at the back of the classroom, after I had hurried through the days class work. I never really knew why her books had stood out to me as much as they did, I never really thought about it, I just knew that I loved them.

But today, as I was reading through The Emotional Craft of Fiction, it dawned on me. Picoult was doing what Maass had described right at the beginning of chapter one. She wrote in such a way that the reader would be able to experience their own unique journey, just like Maass talked about. That is why Picoult herself, not any single book, has stayed at the top of my favorites list.

I can say that I definitely saw a similar version of that writing style in Cathedral. The story was described to us, very vividly, and there was some mental commentary throughout the storytelling; but the gritty details of the narrators feelings were mostly left out. I was able to infer what they were feeling, and put myself in the narrators shoes, even if they were shoes I may never have worn myself. I can’t personally relate to being weirded out by blind people, or by interracial couples; but I was able to develop my own interpretation of how the narrator was feeling about the situation he was put in. I think that the most unique thing about the authors writing style was that I was able to piece together a general idea of the time in which this took place based of the internal monologue of the narrator.

Overall, it was actually a very interesting piece. I really enjoyed the flow of the narrative, and the change of heart that the narrator experiences as he confronts a situation that makes him uncomfortable.

Christy Barrett

In ‘Cathedral’ by Raymond Carver, we have a story of sight and understanding. Of the comparison of depth versus shallow perspectives. Robert is coming to visit after not having seen the narrator’s wife in ten years. They have kept in touch through audio correspondence, but we see that theme of “looking”. The narrator, though he’s never met the blind man, but based on what he’s seen in movies, he already dislikes the man. In this piece, there seems to be a theme. Looking and seeing are perceived as acts of engagement. I noticed though that while the narrator sees the act of seeing as superior, he neglects to see past the superficial… he only sees what he sees instead of going deeper. The character, Robert, seems to understand the narrator’s wife although he can’t physically see her. However, the relationship of the narrator and his wife are brief exchanges and seem shallow. There is an awakening when the narrator and Robert draw pictures of the cathedral. It is the narrator who gains insight, but Robert seems to as well having witnessed the narrator’s epiphany. The narrator seems to then have a better understanding of his own story, in a sense. I found the story telling itself to be rough to get through as it was broken up quite a bit, but I liked the general themes. It seemed like the unveiling of a learning experience to me.

Kyleigh McArthur

Raymond Carver writes in a way unfamiliar to me. He has to write from the point of view of someone who has a prejudice against blind people, someone who is unfamiliar and new in a situation that he wasn’t every expecting to be in. He follows his rules when he wrote this story because he used his own voice and didn’t try to sound like anyone else. The story is written in a style that is unique to him and isn’t a copy or mash up of styles from other authors. He also has written this story by creating a sort of tension within it, but without actually stating that there is tension. Carver leaves it up the us readers to feel the tension, to experience what he is trying to write, but does so without explicitly telling us what we need to be feeling. It’s clear that there is this tension between the husband and the blind man, and there is also tension between the husband and his wife. It seems he is jealous of how close his wife is with the blind man, or at least I believe that is what we are supposed to be seeing. The end of the story still has this feeling left lingering of us readers not getting the ending we were expecting. We are left still curious about the relationships in the story, which I think is what Carver intended and what he thinks makes a good short story.

Miranda Reynolds

What really stuck out to me in this piece was the unexpectedness of what the husband, the point-of-view character, was feeling throughout. This aligns well with what Maass writes in the “Emotional Craft of Fiction.” To get the reader to feel the big primary emotions, one solution is to make the character’s feelings surprising so the reader will think about how they would have reacted in the same situation. Then, no matter what stance the reader takes, they still cannot help but feel something.

In the beginning of “Cathedral,” Carver sets Robert, the blind man, up to hold many complex emotions for the husband. It is obvious, through the adoration of the wife and his own stereotypical assumptions about the blind, that the husband is extremely conflicted in his emotions. Instead of just fixating on anger though, Carver chooses to fix on the husband an indifferent attitude toward what other characters admire in Robert, his kindness and patience. This caused me, while reading, to feel the anger that I was “supposed” to feel at the resistance of the husband. It was a characteristic example of how using those more obscure feelings and deeper emotions allows the reader to feel more emotionally involved in the outcome of the piece, no matter what stance they take.

Something else that Carver does well is how he uses his own fiction advice on short story conclusion. He leaves the reader with something to think about in the end. It is not certain how the husband’s attitude has changed about Robert, if at all, which is what leaves the story lingering in the reader’s mind. Carver advises against overstaying as a writer because this is what gives the reader something to consider, and therefore remember, after putting the book down.

Adeline Knavel

Fiction has always been my favorite genre to read when I was growing up, my favorite book series and teenage fantasy book series was Harry Potter, I then started to read fiction series that had to do with mystery, murder, and drama. After reading “Cathedral” by Raymond Carver we can see he uses his writing skills to describe what was happening to us, we can sort of assuming that he might have something against blind people. I can tell he has something against blind people or he has something against the gentleman that is coming to visit them because he refers to him as the blind man. To me referring to someone as their disability just seems rude and unkind. Raymond Carver writes in a way that makes the narrator dislike the blind man. I could tell he especially doesn’t like the blind man when he was listening to one of his tapes and the blind man starts to talk about him, the narrator then yells “I heard my own name in the mouth of this stranger, this blind man I didn’t even know!” Raymond Carver writes in a way that left us, readers, with something to think about, did the narrator’s feelings towards the blind man change? The ending of “Cathedral” leaves us with wonder, the attitude and feelings of the husbands are never mentioned if they change. This writing style, this fictional story is what draws the reader in for more and wanting the reader to read more and see what happens.

Devin Byrd

Carver does an excellent job of following his own advice. His characters and their emotions are clearly described, understandable, and easily relatable. There was nothing in the story I found unexpected, mysterious, or riveting, so I suppose he succeeded in writing a story bereft of “tricks”.

The thorough context and history he provided before progressing in the narrative left absolutely nothing to be imagined, and there was nothing to be questioned besides the visiting blind man.

Carver made it very clear that the entire story revolved around the main character’s unease relating to the blind visitor, and the metaphor regarding the nature of the main character’s ignorance and the cathedral were not lost on me.

Ainsley Smith

In Maass’s book, “The Emotional Craft of Fiction” we learn that the reader should be taken on their own individual journey: determining emotions, making connections, etc. In “Cathedral,” the reader understands the narrator’s prejudice of the blind man and how he is unhappy to have him in his house, but the emotional state seems to be left out of the text. The reader was able to channel their own emotions: anger, disgust, etc. like Carver intended. The reader was able to feel deeper emotions, like Carver wanted, making the reader more invested in the story being told. Even though the text is fiction, the reader has real emotions that are caused by the nature of the story.

Another thing that was mentioned in “The Emotional Craft of Fiction” is that there is a want for the protagonist (or main character) to be good. I was more intrigued by the story on the sense that I wanted the narrator, a prejudice, judging man, to become a good person. I was more invested in the story because of that hope, like Maass said in his book. In the end, it is unclear if the narrator had many any emotional changes. It was not something that is usually expected, which lead me to ponder it.

We are left with our own thoughts. We can’t help but think about the story even if it is over. Like Carver mentioned in his essay, “Principles of a Story,” we are left with curiosity. It leaves us to think about if the narrator’s attitude changed towards Robert. What was he feeling in that moment where he finally closed his eyes? The reader is left to consider the nature of the short story, which makes the story a success for Carver because it lingers with the reader.

Nadia Finley

There is a great arc to Cathedral. Though I thought that the set up of the husband’s jealousy felt a bit long, it all payed off in the end. The story very well follows Donald Maass’ strategy of setting up emotional expectations and turning them around through narrative. All the irritation the readers sense from the husband towards his wife’s friendship with Robert, in the end, becomes morphed and mixed with indifference, curiosity, unease, and wonder.

Much of the emotion was conveyed through stressing certain points that the husband notices (The blind man toughed his wife’s face, her neck. His wife was still smiling as she got out of the car with the blind man). Other emotion was given through the husband’s own thoughts on things (The poor blind man! His wife died never being able to receive a compliment for her beauty!). These passages, given in “inner” mode (to borrow Maass’ language), mixed in with various passages given in “outer” mode (as the one describing how the husband stays up as late as he can to avoid unsettling dreams) present a state of being that feels as though we are only seeing a small snippet of the husband’s broader life.

At first, on discussing how Carver follows his own advice, I wanted to say that I thought that there were a few places that gave too much information. But, looking back, I see that most of that information was needed to contextualize the narrative or develop character. Though one point that still feels out of place for me is the passage detailing the wife’s past marriage. Development of the wife is justified by her role in the story, yet, other than to highten the husband’s jealousy in some way, I see no need to give so much detail about her past, particularly as this information is not used further on in the story. All else seems to follow the advice given in Carver’s essay. The story feels original, not recycled; the words are practical, not flamboyant; and the details are full-hearted, not rushed.

Boy, was that ending something! The feeling of apology and helplessness from attempting to describe a cathedral turns to wonder in such a smooth way that I did not even realize the shift in mood until the peak of the emotional crescendo. Robert’s constant encouragement, the husband’s gradually lifting spirit, the imagery, the wife’s confusion, the feeling of “I’ve never done anything like this before in my life.” I think back to that section, and I imagine a symphony building up to a soaring melody. Just, wow.

Maass was right. I don’t think that I will forget this story very quickly. I felt it.

Jewel Blanchard

Reading Raymond Carver’s advice he offers on fiction, he states, “Get in, get out. Don’t linger. Go on.” So I very quickly thought, Carver is not taking his own advice when it comes to “Cathedral”. But low and behold I was wrong. He does an excellent job of getting in and getting out. He doesn’t linger on. The way he ended Cathedral was perfect. He later states in his advice on fiction, “There has to be tension, a sense that something is imminent, that certain things are in relentless motion, or else, most often, there simply won’t be a story.” I think he did very well at this. He opens his short story, Cathedral, with jealousy. He also does very well at what Maass discusses in Emotional Craft, which is giving the readers inner mode as well as changes and growth happens and that is the story. What the narrator is feeling and seeing him grow. Again, Carver starts Cathedral with jealousy and as the story goes on with the help of alcohol and weed, the narrator grows and is able to release the jealousy he has with the blind man. At the end, Carver doesn’t open his eyes and he states, “My eyes are still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything.” That says a lot. You are able to tell that he finally let go of what was holding him back which was jealousy. Like Carver states in his advice, it is what is implied that enhances the story and that’s what we see at the end of his short story, Cathedral.

Johnny Bishop

Like some of my classmates Carver is foreign to me. The fiction that I was into when I was younger relatively revolved around fantasy fiction so reading through this weeks material I couldn’t help but keep reading when I got into the story. He did very well at describing how he felt about the situation as well as how open he became by the end of the piece. He went from being kind of evasive about the blind man to being completely engaged with the man. He made it into a story that gripped the reader and made it easy to want to continue. The description of Robert was very detailed and it made it easy to picture the man in the story. I think he incorporated his ideas very well into this short story and I really liked how he ended the story.

katie hopper

It’s really hard to learn about about how to write without learning how to read and to read about writing you obviously need to read something that was written. I wanted to read more after I read Carver’s piece. Short stories have an addictive quality to them, good short stories anyways. Although I will say Cathedrals creeped me out and I don’t know if that makes it good or bad but I think it mostly just wasn’t my taste or something I would usually read but in conjunction with his piece about how to write a short story it did do all of the things and work well. The characters were just too creepy to me but that’s also what made it good writing and he did succeed in evoking emotions.

I read principles of story before I read Carver’s own story. I really liked “Principles of a story” and by the time I got to Carver’s story I forgot most of what I had just read and started to read Cathedral. I went into the story, as we all go into stories, with a blank canvas of a mind. I wasn’t reading it as a writer, looking at his words and his perfect periods, all of the careful placed punctuation. I was just reading it to enjoy the painting it he carved into my mind. His story was matter of fact and honest and I fully felt that “some feeling of threat or of menace” he was talking about. I always forget how much I love short stories for their ability to suck you in and spit you out anew.

It was interesting to see Carver talk about the thing he does, the art he makes in sort of formulaic ways, which The Emotional Craft of Fiction aims to do as well. But at the same time it’s anything but formulaic because they’re only identifying strategies, patterns in the placement of words that many authors fall into – but they don’t tell you what words to use, just some tools in your toolbox to lend your brain to the right one. I think it would be useful to re-read both of his pieces and then go back to the Emotional Craft of Fiction to try to understand what they’re telling me to do.

This is just reminding me of the magic of short stories!!!

Andrew S.

Many of the qualities mentioned by Raymond Carver throughout his “Principles of a Short Story” are qualities that, while subtle in their execution, seem to be present in a majority of the literature with a long shelf life– that is, literature I could read time and time again, often regardless of the time period from when it was released. While almost nobody in the modern Western world has a life that is, in any way, relatable to the characters and events portrayed in Beowulf– the text’s longevity is undoubtedly aided by the quality of its writing. Some of its traits include ones mentioned by Carver, millennia before Carver could quantify it: “Clear and specific language” (kennings in Beowulf’s case), and “a feeling of threat or sense of menace” (the constant threat of a violent death by various monsters) both serve these purposes. I use Beowulf only as an example of how a story is made more interesting and re-readable by containing the traits outlined by Carver, but what about Carver himself and his works?

Reading “Cathedral”, I was able to identify examples of practically every tidbit of advice documented in his “Principles of a Short Story” piece. But the one trait in particular that stuck with me was not just the tension created by the presence of the blind man, Robert, but how the initial mystery and uncertainty the narrator had about him was a large part of what created it. In “Principles of a Short Story”, Carver states: “What creates tension in a piece of fiction is partly the way the concrete words are linked together to make up the visible action of the story. But it’s also the things that are left out, that are implied…”. We, the reader, never got to hear how the audio tape ended, as the narrator and his wife were interrupted. This created tension about the personality and intentions of Robert, whereas, had we been told everything, there would be nothing to speculate about– nothing to worry about.

Another trait I noticed within the story was how the tension served to propel the story forward, or to increase “circulation”. If the narrator’s thoughts about Robert hadn’t evolved, there would be no story. But as the story goes on, there is more interaction between the two and more character development. In the eyes of narrator, Robert transitions from the scary unknown, into a friend to smoke pot with, and then into somebody to confide in and have intimate experiences with, like the joint-drawing of the cathedral at the story’s conclusion.

The Gustav Freitag plot pyramid posted above is satisfied throughout the events of the story, but it could not have been done nearly as effectively without Carver using the literary techniques he outlined in his essay. Essentially, Raymond Carver’s tips are utilized within “Cathedral” to create the necessary tension to move the story along, increasing or decreasing detail and ambiguity in order to control the story’s pacing.

Ta'Mariah Jenkins

To be honest, I’m not a huge fan of reading fiction so when realizing that the is the unit we were going into, I was a bit worried. I like to keep it real and fiction is a spark of creativity that it’s hard for me to pull out ideas without inspiration. With creativity, there could be a lot of meanings and different understandings In addition to different outcomes and probabilities. Developing personalities and moods for characters. As well as creating a basis and storyline that correlates with these characters. Such as the “Cathedral” by Raymond Carver.

The basic storyline in this story is about the wife’s blind friend and the narrator, who’s the wife’s husband. When first reading this, I couldn’t understand the objective of the story or where the writer was coming from, so I was taken aback and didn’t know how to respond. it took me five days later to reread the story and understand that it wasn’t supposed to be a hero to villain story, but a perspective story on the words of looking vs seeing something. For example, the wife. You can tell the wife and husband don’t have a closes relationship throughout the story, but the way she handles Robert with care is not obvious, but subtle. Moreover, I believe that because he listens to her on a deeper level compared to her husband. He obviously feels threatened by Robert and needs to bury that insecurity by feeling superior through his sight.

However, after being told to draw the cathedral without looking, I believe the narrator notices the insight of seeing instead of looking. The feeling of knowing where you are, but not being anywhere. Looing past things in order to find the deeper meaning. I really liked this story after giving it some time think and understand it.

Casey Fetterhoff

Fiction is my favorite thing to read, so I’m thrilled to be entering this section of the course. The Freitag’s pyramid is something I think we can all recognize in stories that we’ve heard or told, even without consciously acknowledging it. When is the last time you left a story on a “cliffhanger?: Even if it was about an incident at work, or something personal, people tend to tell stories in a more-or-less similar fashion to Freitag’s pyramid, and that’s one of the fascinating things to me about our brains and how we process and regurgitate information.

Carver’s story makes great use of tension, in several ways. The presence of Robert, the narrator’s thoughts about him, and the developing story all use tension to drive the story forward, and build it appropriately in a way that is effective to tell a story. I think focus has a lot to do with tension as well. For instance, a narrator focusing heavily on a specific thing, seems to imply tension-or passion, in some cases. In this case, however, the “what is left out” that Carver references in his essay, implies that the focus (what is left in) is so important that it is what creates the tension in itself. Is there tension in every good story? I think that depends on what type of reader is reading it. Some readers want relaxing stories, with no suspense or tension, whereas others (like myself) are always wondering what will happen next. After all, why do people ready the same books over and over if the tension is the best part of the story? where is the tension in a story you have memorized?

Zachary Macintyre

Reading Carver’s short story, “Cathedral”, I really like the design of the husband’s character. He is noticeably dislikeable but is designed as such intentionally, and not in such a way that it made me want to stop reading. Rather, it drew me into the conflict between him and his own callous, antisocial nature. In just a few pages, the husband begins a noticeable, yet not unnatural change. I can also very easily picture Carver not having known the ending of the story when he came up with the beginning, as the flow of the story appeared very organic, and not forced. The short story format is also great, particularly for someone like myself who has a very short attention span and is apt to bounce away from a project, only to rediscover it weeks or months later among its hundreds of discarded brethren. Carver uses the short story format to provoke a powerful emotional response before the mind is able to bounce away to something else, and also successfully holding the reader’s attention throughout it’s duration.

Gabriel Miller

Carver’s short story utilizes the manipulation of details and perspective as outlined in Maass’s ideas of emotional craft because the simplicity of meeting a stranger is used to expose the narrator’s insecurities and his development. There is a balance of high and low concepts in the story such as what does it meant to see and jealousy respectively. In high concepts, the manipulation of subtle details are used to create a lasting pattern that is strong enough for readers to pick up on early into the story. For example, the ideas of vision are clearly expressed in the narrator’s musings on how awful it would be for a husband to be oblivious to their wife when he is more oblivious than a blind man. This idea is an example of Maass’s concept of having direct emotion from a character reflect themselves in complex ways instead of simply being literal.

The story’s focus on the simple premise of meeting the unfamiliar follows Maass’s ideas on the value of developing small or common things. The small scale of the story works lends to a short story because it then allows for the author to focus on important details. The story is strictly focused on developing the tension between the narrator and the blind man and later exploring their confrontation. This succinct concept follows Carver’s own advice on the nature of short stories capturing fleeting or small moments as well, as the main focus is on how the idea of cathedrals are expressed to each other.

Zofia Sheesley

I love how the beginning sounds like a guy just telling a story to his friends, just totally casual. There’s a tone of boredom or frustration like he’s been told or has told this story a million times, there’s also just a very clear and concise shorthand way that its written and that alone sends a message and sets a tone and it’s all causal and whatever and then all of a sudden she tries to commit suicide. But the tone never changes. And it’s still casual with a hint of annoyance and then he drops the mystery of the blind man’s review of him from way back when, a total cliff hanger. But again, no tone shift, Just casual. And then he drops in some racist remarks. This story is so frustratingly casual and that makes it so real and authentic but its not real at all and THAT is frustrating. There’s almost a hateful tone to it all when he starts talking about Beulah, not necessarily hate towards Beulah herself but the blind man and the blind man’s relationship with the story-teller’s wife. There are so many complex emotions hiding in this. As soon as we learn the bllind man’s name, Robert, the storyteller calls Robert’s marriage and life and wife’s death “pathetic”. There is so much hate in this story. But still he tries to be nice and welcoming to the Blind man, for his wife, because he clearly loves his wife. The dialogue is funky, it’s repetitive and anxious but it fits. I feel really indifferent about this piece as a whole, I still think the story teller is a jerk and I love that the blind man was trying to work with him and get him to come out of his angry shell and at the end they almost found an understanding. But overall the main man is still a jerk.

Anna Johnson

I really enjoyed this fictional short story by Carver. I was wrapped in from the beginning wondering who this blind man was and I was curious about the wife’s relationship with him. At first, I thought that the narrator was jealous but that was not the case at all, he surely didn’t like him for no reason at all. I think we see a lot of emotions from the narrator and it built up to a well-learned lesson. In the beginning, he only thought of Robert as the blind man, and only that, it might be safe to say he was disgusted with him. By the end, he was put in Robert’s shoes, and it’s probably something he least expected.

It was easy to not like the narrator because of his shallow thoughts towards the blind man. As a reader, I felt sorry for the blind man and his loss of his wife, I wanted the narrator to see that even though he is blind, does not make him less of a person. As there was continuous contact between the wife and blind man I always thought about them being more than friends, but she was only a ray of sunshine to this blind man and nothing else. They were meant to meet and keep in contact.

The dialogue of the story was appreciated as a reader because it helped tell the story. It helped characterize Robert and the narrator. I wasn’t sure where the story was going to go by the end but I was pleasantly surprised that Robert and the narrator had some bonding time. Robert has had a tough life and I am not sure how to feel about the narrator, I hope he was able to think more than what’s on the surface.